Remembrance Sunday: A British Muslim perspective on honouring all those who fell

Recently, I spoke to a friend who works in diversity. She said that she’d only just realised for the first time that large numbers of Muslims had fought in the two world wars to support Britain.

This is someone who spends her professional life thinking about integration and inclusivity, yet she said that it had led to quite a profound change in how she thought about British history and identity. She said if more people knew about the shared history, it would be a powerful bridge between communities.

That also got me thinking about the subject and reflecting on my own personal experiences. The scale of the losses, the terrible conditions soldiers fought in, were taught to me in history lessons, and reflected in many TV programmes and books I was exposed to growing up.

This had a profound impact on me. Learning about the horrors of war and especially the Holocaust in World War II, made me ask questions at a young age about God, as well as the nature of human beings. My decision to study psychology and become a psychotherapist was shaped by this questioning. It has also contributed to my political stances – around when war is justified, when it is not, and my ongoing passion for social justice and anti-racist struggles.

As a child of Pakistani immigrants, only seeing the contribution of white Britons to war efforts, I was not made to feel that I had any direct connection to the commemoration events. Despite my father telling us that his father had served in the merchant navy and that his ship was bombed, I was not able to connect my grandfather to the larger story of the war and the acts of commemoration we hold as a nation.

If anything I was left slightly uncomfortable – resenting the pressure to ‘prove’ some kind of loyalty and gratitude over and beyond that of my fellow citizens, whilst having my sense of belonging continually undermined with narratives such as “Muslims have never done anything for us”.

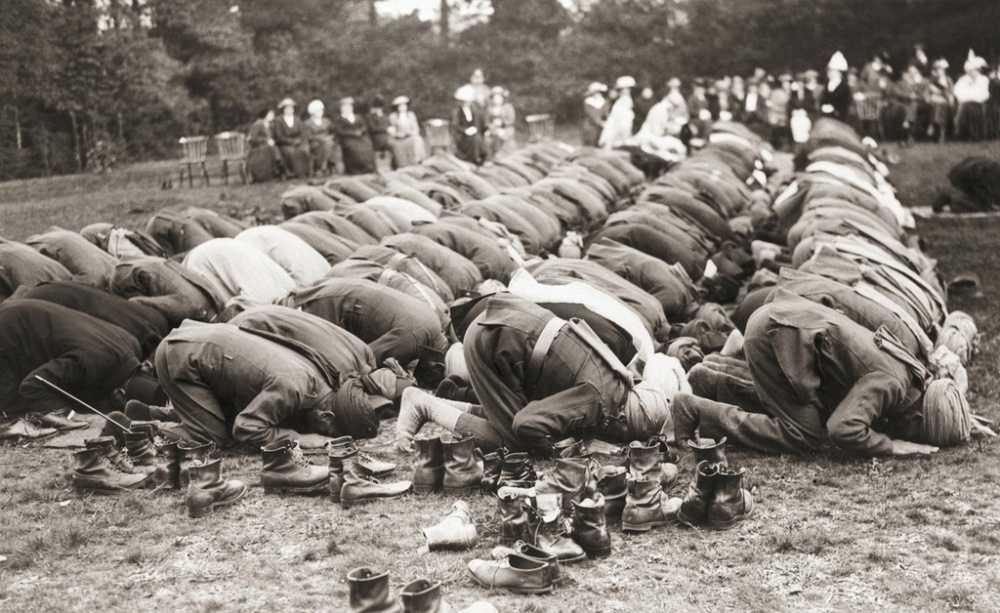

Hulton Archive

Hulton Archive This was compounded by a confusing combination of an awareness of some of the ugly brutality of Britain’s colonisation of India, the pain in Kashmir its ongoing legacy, and the pride of my parents in all things British. This dissonance was endearingly manifested every speech day at school when my father would enthusiastically (and loudly) sing “God Save the Queen” – despite a deeply held stance against the violence of British Imperialism.

I confess my own ignorance of the scale of the contribution of Muslims to allied war efforts until fairly recently. I was taken aback when I learned the actual number – 2 million Muslim soldiers and labourers. I found it particularly striking that so many volunteered to fight in a European war not of their making, nor of direct benefit to their country of birth, and were prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice to defend Britain in its time of need. The fact that they, alongside other ethnic minority volunteers, have been so little remembered – their contribution having been virtually ‘white washed’ out of much ‘official’ history – is tragic and wrong.

There have been efforts in recent years to raise awareness of the part that Muslims have played. This is now leading to a slow and steady increase in knowledge on the subject, although to say that it is now mainstream would be a massive overstatement.

The Forgotten Heroes 14-19 Foundation has done a sterling job of painstakingly documenting facts about the millions of Muslims who fought to defend Britain. The Muslim Heritage Trust is working with them to spread the word in the UK, but it is still likely to take some time to break through into the national consciousness unless a radical step is made.

This year, British Future’s Remember Together initiative has led to Imams giving remembrance-themed services at Friday prayers and coming together to learn about the Muslim contribution to WW1. This is a great start to engaging the Muslim community and Imam Qari Asim will be at the Cenotaph commemorations in London along with other faith leaders. He wrote eloquently on the importance of recognising our shared history and the need to counter the far-right narrative of claiming that Muslims have no place in Britain by working for more peace and understanding among all the people living in Britain today.

The contributions of commonwealth citizens to the UK’s safety and prosperity didn’t start with the Windrush or after the war had finished, they go back much further. We need this to be taught in the school curriculum and we need coverage of the commemorations to be more diverse, reflecting the fact that the war effort was not carried out by an army of white Britons, but in fact it resembled much more closely the ethnic mix we have in this country today.

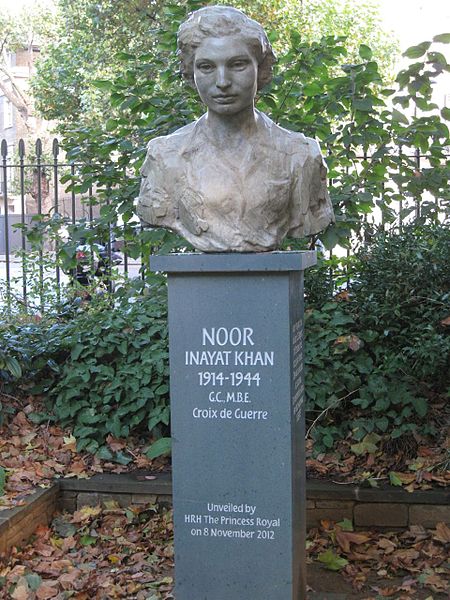

HMSO

HMSO Another way to help make that leap from a small minority of people recognising the contribution of Muslims in our shared history to everyone being more aware of it, is to support a campaign for the new £50 note to feature Noor Inayat Khan – a Muslim war heroine who died protecting Britain’s secrets in WWII.

Her story of great suffering and immense courage is an inspiring one. When the Nazis occupied Paris in 1940, Noor volunteered for the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. Aged just 29, she ran Churchill’s resistance network in occupied France. She was in charge of communicating secret wireless messages to and from London. She helped 30 downed airmen to return to safety. Sadly, she was betrayed and captured by the Gestapo, but she refused to reveal any British secrets.

She was tortured, whilst being chained in solitary confinement, and then eventually taken to Dachau Concentration Camp. Noor was executed in the early hours of September 13, 1944. She was posthumously awarded the George Cross, Britain’s highest civilian decoration in 1949 for refusing to abandon “the principal and most dangerous post in France”. She was only one of 3 women in the SEO to be awarded the medal. The other two – Violette Szabo and Odette Hallowes – are better known and more widely celebrated until now.

Henk van der Wal

Henk van der Wal Valuing Noor Inayat Khan’ sacrifice in such a prominent way would be a vital step in redressing the gap in collective memory and towards recognising that we would not have the freedoms we now enjoy in Britain, without all the sacrifices that were made by people of all colours, races and religions. Along with many others, I am supporting this campaign and urge you all to sign the petition.

My prayers this Armistice day will be that by learning from the horrors of the war that was supposed to end all wars, we can work together to build a lasting peace. Now, more than ever, we must understand the value of people’s contributions from across the globe to counter nationalist voices attempting to re-write history. They want us to forget and erase Muslim sacrifices from history. We must honour and remember all those who fell.

An article by Salma Yaqoob | @SalmaYaqoob